The Passchendaele offensive

This article was written by Lode Notredame, a former member of the Society’s board. Lode was born and raised near the Passchendaele battlefields and he has an intimate knowledge of its terrain and history. His writing focuses on the battle and its aftermath.

Lode’s article here in some ways duplicates “Passchendaele in the context of WW1” written by the Society’s late former President, Iain MacKenzie. Iain’s father fought in the Battle of Passchendaele. In his article, Iain steps back and views the Battle as part of a broader picture, first telling us how the Great War came about before he moves from Gallipoli to other landmark battles then finally focusing on Passchendaele.

On the Friday morning of 12 October 1917, 846 young New Zealanders were killed in the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium. By the end of that day the total number of casualties - the wounded, the dead and the missing - was 2,740. Over the coming days, many more were to die from the wounds they suffered. It took two and a half days to clear the battlefield of the dead and injured.

If you mention World War 1 to most New Zealanders, they will immediately think of Gallipoli where 2,700 of our soldiers died. Some will mention France – there, another 2,000 died. But most do not realise that the New Zealand Division spent a year of this war in Flanders Fields in Belgium where a further 5,000 died between 1917 and 1918.

The numbers just mentioned amount to 0.84% of New Zealand’s then population of 1,150,000. That percentage against our population today is more than 42,000. Imagine it – the scale of the loss! These numbers speak to the enormity of our country’s sacrifice. Our men came from “the uttermost ends of the earth” to the scenes of battle and suffered one of the highest casualty counts of all the countries involved.

Over 4,600 New Zealand servicemen lie in the Fields of Flanders – most buried in one of many cemeteries, but a great many still lie beneath that once ravaged soil. All are commemorated in as many as 80 cemeteries and on memorials found throughout what was known during the war as the Ypres Salient.

Since 1917, Passchendaele has been a byword for the horror of The Great War. The name conjures up images of a shattered landscape of endless mud, never ending rain, shell craters and barbed wire, trenches, and of helpless soldiers mown down by machine guns and artillery.

Where they lie

The entire 3rd Battle of Ypres lasted 100 days and cost the British Expeditionary Forces 245,000 men.

Many of those who died during the Passchendaele Offensive are buried or commemorated at Tyne Cot Cemetery at the village of Passchendaele. Within its flint walls and embracing arms are the graves of almost 12,000. The entire rear of the cemetery is occupied by a curved Memorial to the Missing commemorating a further 35,000 soldiers who have no known graves. It is the largest Commonwealth Cemetery on the Western Front.

Tyne Cot contains the graves of more New Zealanders than any other cemetery beyond our shores. Here you will find the names of 1,696 of our men – 520 graves and, on the New Zealand Memorial Apse on the curved rear wall, the names of 1,176 New Zealanders who have no known grave. These numbers do not include the names of those who died in field dressing stations and hospitals behind the lines, well after the date of being wounded

In addition to Tyne Cot, there are another two New Zealand Memorials to the Missing in the immediate vicinity – at the Messines Memorial and at Buttes Cemetery, Polygon Wood which is close to Zonnebeke.

The first step - Messines

The push to Passchendaele

But Gravenstafel and Broodseinde first . . .

Then the darkest day

Where they lie

The aftermath

After 1918

But Gravenstafel and Broodseinde first . . .

Before the devastating defeat at Bellevue Spur on 12 October, there was a successful assault on Gravenstafel Spur. The New Zealand Division was called upon to fight in the Battle for Broodseinde on 4 October - the Australians were sent up the Broodseinde Ridge and the New Zealanders objective was Gravenstafel Spur, the first of two small rises leading to the Passchendaele Ridge.

The New Zealand Division fought alongside eight British and three Australian Divisions along an eight mile front. Although successful, the Battle of Broodseinde was not without cost. There were around 20,000 killed or wounded on the Allied side and the Germans suffered similarly. The attack cost the New Zealand Division 1,700 casualties and more than 450 lives – including that of the 1905 All Black captain Dave Gallaher.

Grave of an unknown soldier

General Herbert Plummer

1905 All Black captain Dave Gallaher.

Private H.J. Nicholas

The first step - Messines

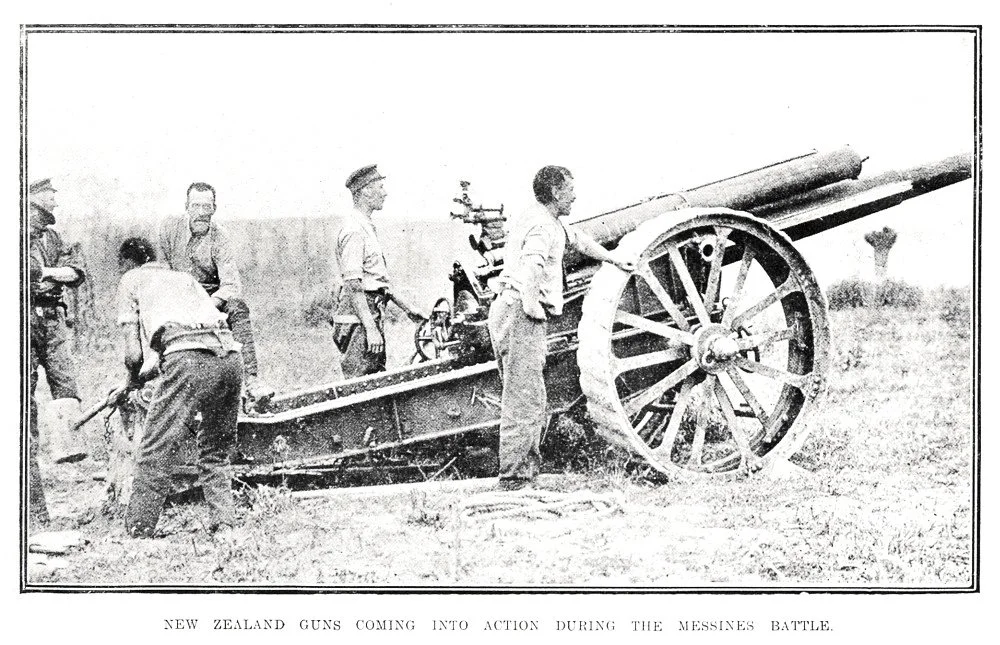

Before the Passchendaele Offensive could be launched, one important preliminary step had to be taken - the removal of the Germans from the Messines Ridge to the south-east of Passchendaele. Unless this was done, the enemy would be able to observe preparations for the major offensive coming up to Ypres from the south. General Plummer was in charge of the battle and he planned a bite-and-hold operation – an attack with strictly limited objectives. The New Zealand Division was among those selected for the assault on the Ridge and the village of Messines.

The carefully prepared attack was a striking success.

It began at 3.10am on the morning of 7 June with the coordinated explosion of 21 huge mines placed by engineers who had tunnelled under the German lines (some 10,000 Germans were killed and so loud was the explosion that it caused an earthquake and was felt in London). The initial assault went to plan and by 7am the New Zealanders had cleared Messines of the enemy, with relatively few casualties. However, as the day wore on, German guns began to bombard the newly captured areas with increasing ferocity. The battle continued for a week and the New Zealand toll was high. By the time the Division was relieved it had suffered the loss of 700 dead and more than 3,000 wounded.

Following the successful attack on Messines, the Germans launched a number of counter-attacks, only to lose more ground. At the end of July, the New Zealand 1st Brigade was involved in battles at Warneton and at the crossroads known as La Basseville, a few kilometres south-west of Messines. The main objective of these attacks was to create a decoy from the preparations taking place near Passchendaele. The New Zealanders suffered serious casualties during these actions

The aftermath

The New Zealanders were not done with Belgium yet - they continued to operate in the Ypres area until February 1919. They took part in another attack at nearby Polderhoek from 3-6 December. The objective was to capture the dominating Polderhoek Spur to prevent the Germans from threatening the New Zealanders’ trenches to the north. About 80 NZ soldiers lost their lives and hundreds more were wounded. The missing are commemorated on the memorial at Polygon Wood. The futility of the attack was underscored nine days later, after the New Zealanders had withdrawn from the line, when the Germans regained all the ground they had lost on 3 December.

The battle ended on 6 December but did not stop fully as the two sides continued to exchange fire. 129 soldiers of the 1st Battalion were killed during this ‘quiet’ period in December.

The Victoria Cross was awarded to Private H.J. Nicholas for his exemplary conduct during the assault at Polderhoek. He died almost a year later at Le Quesnoy in France, 19 days before the Armistice.

Other VC recipients from the Belgium campaign are Samuel Frickleton when on 7 June at Messines he single-handedly attacked two machine-gun posts, killing their crews. And Leslie Andrew who also captured two machine-guns on 31 July at La Basseville.

Early in 1918 the Germans launched their great spring offensive. The New Zealand Division was rushed back south to Amiens in France. Their last action was to capture the ancient fortress town of Le Quesnoy in November 1918.

After 1918

The cost in lives for two and a half years on the Western Front in France and Belgium was appalling. Altogether some 13,200 New Zealanders died of wounds or sickness as a direct result of this campaign, including 50 held as prisoners of war and more than 700 at home. Another 35,000 were wounded and 414 prisoners of war were ultimately repatriated. The total casualties were close to 50,000, well over half the number of those who served on the Western Front. 103,000 troops and nurses signed up to go to war from a population of some 1,150,000. There were 9,521 casualties in total including the dead, the wounded, the sick and those who died in training or as a result of their injuries within five years of returning home.

In the years following 1917, New Zealanders remembered the sacrifice of Passchendaele and other battles in a variety of ways. Many returned servicemen suffered in silence, wracked by nightmares and lingering wounds. Families mourned lost loved ones in private and through public rituals. The most visible symbols were the hundreds of war memorials erected by local communities across the country. These became focal points of a shared sense of sadness and pride, but they also became surrogate tombs for those buried in far-away Belgium.

We should remember the Battle of Passchendaele – a huge tragedy, as that battle most particularly symbolises the futility and cost of war. As a “City of Peace” Ypres is a city of remembrance, never forgetting the tremendous human cost of WW1 to soldiers and civilians alike. For decades and decades, each and every night at 8pm the traffic passing through the Menin Gate has stopped while the Last Post is sounded in memory of those who lost their lives in the Ypres Salient.

As a tribute to the New Zealanders who still lie in the soil of Flanders, whose sacrifice with that of others in the Great War, helped preserve the rights and freedoms we now take for granted – we must remember them.

If the words “Lest we forget” are to have any meaning, the names of the fallen, and the battles in which they fell, must forever be remembered.

This website is a tribute to the New Zealanders who never came home and still lie beneath Flanders Fields, whose sacrifice, with that of others in the Great War, helped preserve the rights and freedoms we now take for granted.

From Gallipoli and the Somme

After the withdrawal at Gallipoli, the New Zealand Division’s first battle on the Western Front was in France on the Somme river in 1916. Between 15 September and being relieved on 4 October, they had advanced three kilometres and captured eight kilometres of enemy frontline, but at the cost of 7,048 casualties, 1,500 of whom were killed.

The Division then moved north to Ypres in Belgium and was heavily involved in the 3rd Battle of Ypres – commonly known as the Passchendaele Offensive, fought from July to November 1917. It was divided up into eight separate battles after the war to recognise the separate feats and dates of each major push.

The capture of the Belgian village of Passchendaele, near Ypres, became an objective that cost the lives of thousands of people, including many New Zealanders.

The ridge leading to the village was the site of the worst disaster in terms of lives lost in our history since 1840.

The push to Passchendaele

The assault on Passchendaele was part of a vast allied offensive launched on 31 July. British Commander-in-Chief Sir Douglas Haig hoped to keep the pressure on the Germans after the great struggle on the Somme the previous year. Haig’s plan involved seizing the Pilckem Ridge and the Gheluvet-Passchendaele plateau to open the way for a drive on the town of Roulers. Once this important transport hub was in allied hands, the British would drive north to the coast to neutralise the German U-boat facilities there.

The British artillery had pounded the German positions with 4.2 million shells in the two weeks before the Battle of Passchendaele. Every tree, house, church and street had been obliterated, the entire terrain between Ypres and Zonnebeke turned into a pitiless, cratered landscape. Head-high craters pockmarked the terrain and were filled with mud so deep and thick that soldiers simply disappeared, never to be found again.

(This helps explain why on the Menin Gate Memorial there are 55,000 names of soldiers who have no known grave and on the Tyne Cot Memorial a further 35,000.)

Then the darkest day

The very darkest day in New Zealand’s military history however came on 12 October during the battle for Bellevue Spur, the second of the small rises leading to the Passchendaele Ridge. This was the 1st Battle of Passchendaele.

The continuing rain had made the entire area an almost impassable quagmire. The toll was horrendous - 846 men lost their lives on just one morning on Bellevue Spur in what was seen as the last obstacle in capturing the village of Passchendaele.

By the time the missing were counted, there were more than 117 officers and 3,179 New Zealand casualties on Bellevue Spur. Because of the state of the terrain and head-high shell holes, it was impossible to rescue badly wounded soldiers lying in the mud between the lines.

New Zealand’s involvement in the Passchendaele Offensive finally came to an end on 18 October when the Division was relieved by Canadian troops. The Canadians went on to capture the village of Passchendaele and Hill 52 beyond in the 2nd Battle of Passchendaele which lasted from 26 October to 10 November.